25 years on: What we learned from ice storm ’98

January 4, 2023

By Glenn McGillivray

Canada’s first billion-dollar insured loss event in 1998 was a wake-up call. Glenn McGillivray takes stock 25 years later and asks, could it happen again?

Photo: Annex Business Media.

Photo: Annex Business Media. Twenty-five years ago this week, Canada’s first billion-dollar insured loss event began to take shape as a unique set of meteorological conditions essentially lead to a days-long conveyor of water being funnelled into the Ottawa/St. Lawrence Valley from the southern United States.

From late Sunday, Jan. 4, to Saturday, Jan. 10, 1998, freezing rain lashed eastern Ontario and southwestern Quebec before heading into Canada’s Atlantic provinces. In Ontario, the storm dumped 85 millimetres (mm) of freezing rain on Ottawa, 73 mm on Kingston and 108 mm on Cornwall. In Quebec, 100 mm ravaged Montreal and parts of the province’s south shore. By Jan. 18, 25 Canadians were dead with a total of 35 lives lost by the time it was all over. Almost 1,000 were injured.

Emergency crews worked around the clock responding to reports of trees pulling down hydro poles and ice toppling transmission pylons. By some estimates, roughly 1,000 transmission towers and 30,000 utility poles were destroyed or damaged. This is to say nothing of transformers, crossarms and other power infrastructure.

Close to 110,000 homes, farms and businesses in eastern Ontario were without electricity. In Quebec, 1.4 million locations lost power – translating into roughly three million people or half the province’s population at the time. At the storm’s height on Jan. 9, more than 10 per cent of Canadians were without electricity with some not having service restored for more than a month.

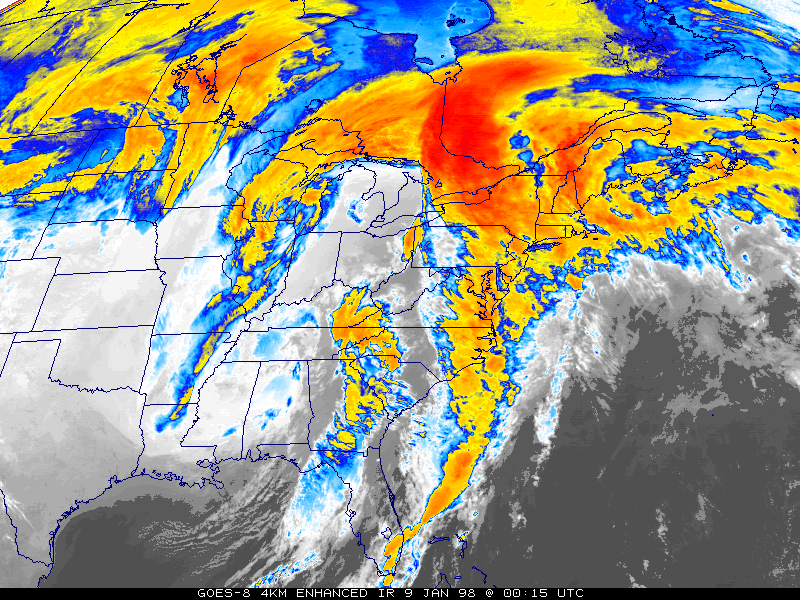

The ice storm’s devastation stretched more than 300 kilometres from Ottawa/Carlton through Montreal to Drummondville, Que. Photo: National Climatic Data Center of United States.

The worst of the devastation stretched more than 300 kilometres from Ottawa/Carlton through Montreal to Drummondville, Que. Scores of municipalities and townships in the affected area declared a state of emergency and the federal government mobilized over 15,500 soldiers in the biggest peacetime deployment of the Canadian Armed Forces in the country’s history.

The severity of an ice storm depends largely on the accumulation of ice, the location and extent of the area affected and the duration of the event. By all of these measures, the 1998 eastern Canada ice storm – also known as The Great Ice Storm or Ice storm ’98 – remains the worst freezing rain event on Canadian record.

Previous major ice storm events in Canada resulted in about half the ice accretion experienced in this event. Further, previous events largely impacted fairly localized, rural areas. But this event ravaged one of the largest metroplexes in North America. Finally, aside from the huge area affected, the ’98 ice storm was unusual because it went on for so long. At the time of this event, Ottawa and Montreal historically experienced freezing precipitation 12 to 17 days a year with each episode generally lasting for only a few hours for an annual average total of between 45 and 65 hours. During this event, the number of hours of freezing rain and drizzle was in excess of 80 – nearly double the normal annual total for many places.

Insured losses from the event topped $1.38 billion (equivalent to $2.15 billion in 2021), making it Canada’s costliest insured loss event by far. It remained so for 15 years, until the June 2013 flooding in Southern Alberta. When including both Canadian and U.S. claims, the event broke the international record for most insurance claims filed from a single event – more than 800,000 – overtaking 1992’s Hurricane Andrew.

Most Canadian companies that insure homes, cars and businesses purchase their catastrophe reinsurance (i.e. insurance for insurance companies) for the calendar year (i.e. beginning on Jan. 1 and expiring on Dec. 31). Many Canadian insurers impacted by the ice storm used up this reinsurance in the first week of the year and either had to purchase costly “reinstatement covers” (i.e. more reinsurance) or “go bare” (i.e. risk going through the rest of the year without reinsurance). This had never happened in Canada prior to 1998.

Economic damage, which includes insured damaged plus everything else, was estimated at $5.4 billion.

The storm woke a lot of people up to the fact that Canada could experience billion-dollar loss events that fall outside of a major earthquake in the Lower Mainland of British Columbia. Indeed, since 1998 Canada has experienced several billion-dollar loss events including flood, wildfire, hail and summer storm.

The event underscored the fact that neither the Government of Quebec nor affected municipalities had disaster plans in place (the latter weren’t required to at the time, this has since changed). While approximately 600,000 people were temporarily displaced by the storm, almost the entire island of Montreal came extremely close to being completely evacuated as there was no emergency power for the island’s water supply.

It also drew great attention to the vulnerability of the electrical grid, particularly in the Greater Montreal area, where a post-mortem of the storm revealed a number of major engineering and design issues with the electrical distribution system.

Could it happen again?

While a December 2013 ice storm in Eastern Canada (including the Greater Toronto Area) cost insurers over $200 million (2013 dollars), an analysis conducted by catastrophe modeler AIR Worldwide for a 2016 ICLR webinar (see the replay here) indicated that another 1998 ice storm event squarely over Toronto could cost as much as $26 billion in damage.

It’s important to note that no two disasters are completely alike and the meteorological conditions that came together in early January 1998 to cause this event were quite unique.

But never say never. We often say in insurance that if something has happened once, it can happen again.

Glenn McGillivray is managing director of the Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction and adjunct professor of disaster and emergency management at York University.

Glenn McGillivray is managing director of the Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction and adjunct professor of disaster and emergency management at York University.

Print this page