A look at Ocean Networks Canada’s earthquake early warning system

June 1, 2023

By

Maria Church

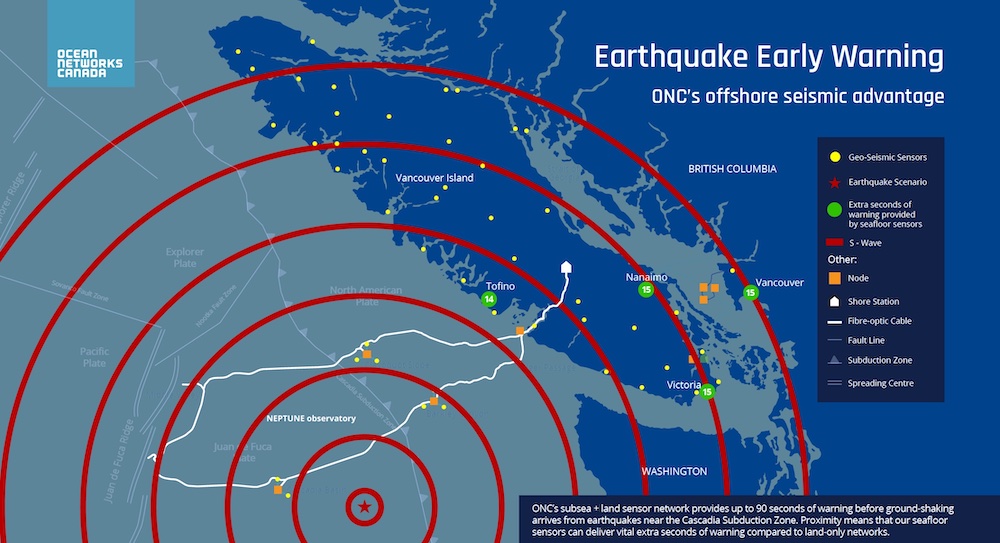

Ocean Networks Canada is nearly ready to launch its earthquake early warning system that monitors the Cascadia subduction zone off the coast of Vancouver Island.

The TitanEA is a strong motion Ethernet accelerograph specifically designed for networked deployments. The TitanEA features the Class “A” Titan triaxial force balance sensor and its industry-leading dynamic range meets or exceeds the performance requirements of any local regulations for sensor specification. Photo: Ocean Networks Canada.

The TitanEA is a strong motion Ethernet accelerograph specifically designed for networked deployments. The TitanEA features the Class “A” Titan triaxial force balance sensor and its industry-leading dynamic range meets or exceeds the performance requirements of any local regulations for sensor specification. Photo: Ocean Networks Canada. In one minute, Vancouver International Airport can direct all arriving planes to reroute. In one minute, B.C.’s hospitals can safely pause delicate surgeries and brace patients. In one minute, cities can prevent traffic from flowing in tunnels or on bridges. In one minute, the transit authority can stop trains in a safe location.

One minute of warning to critical infrastructure operators before an earthquake shakes ground can undoubtably save lives.

In the coming months, Ocean Networks Canada’s (ONC) earthquake early warning system will officially launch after years of development to become among the most advanced of its kind. The unique system uses 35 underwater and land seismic sensor sites to determine an earthquake’s location, magnitude and when the ground shaking will begin.

The system monitors the seismically active Cascadia subduction zone – the meeting place of the Juan de Fuca and North American tectonic plates. The Juan de Fuca plate subducts – or slides – underneath the North American plate at about five centimetres a year. Along with two smaller plates – Explorer to the north and Gorda to the south – the Cascadia subduction zone stretches from the top of California to northern Vancouver Island.

Scientists tell us Cascadia is due for a megathrust earthquake – the so-called big one – that happens every 300 to 500 years. The last quake of that scale was a magnitude 9.0 on Jan. 26, 1700. First Nations oral traditions and geological records confirm the devastation the earthquake and tsunami caused to pacific coastal communities.

University-led system

ONC, an initiative of the University of Victoria, is based in the B.C. capital. ONC has ocean observatories and networks in the Pacific, Atlantic and Arctic oceans allowing for real-time ocean observation, data collection and communication.

Benoît Pirenne, ONC’s director of user engagement, traces the earthquake early warning system project back to 2014 when researchers began a proof-of-concept project with seismic sensors in northwestern Vancouver Island.

“We wanted to test the concept and basically figure out if we could, with even small seismometers – accelerometers in particular – get a sense and have an ability to identify epicentres and magnitudes of earthquakes based on already published algorithms from the research community,” Pirenne says.

Benoît Pirenne is Ocean Network Canada’s director of user engagement.

The project lasted a few years and gave researchers a taste of the challenges Canada’s remote geography posed to more sophisticated sensor systems.

Armed with new provincial funding from B.C.’s emergency management ministry, the ONC team reopened the project with Natural Resources Canada and, by 2019, had a network of sensors in place to monitor the northern fault zone just offshore Vancouver Island.

Work over the past few years involved steps to commission the system, to “verify, certify, make it fool proof, add redundancy and all those things as necessary,” Pirenne says. “As of March 31, 2023, we finished the commissioning of the whole thing.”

System infrastructure

The ONC earthquake early warning system comprises 35 sites onshore and offshore, each with at least one accelerometer, which measures vibration. The sites are about 20 to 30 kilometres from each other and most have multiple instruments for redundancy. Having more instruments than needed increases the chance of the system functioning after a damaging earthquake, Pirenne explains.

“As you can imagine, after a major earthquake, people are not going to be running out to fix your stations. They’re going to be worrying about their home, their family, their own existence before they think about repairing instruments,” he says.

Pirenne says their early warning system is unique from comparable systems in three ways. First, it’s one of only two in the world to include underwater seismic sensors – the other is used by Japan. Locating sensors underwater allows them to be as near as possible to offshore epicentres, maximizing the time available between detection of a quake’s primary waves underwater and the ground-shaking waves felt on land.

Second, the system on land combines data streams from an accelerometer and global positioning system (GPS) to get a better sense of the magnitude of an earthquake. Accelerometers alone cap when measuring earthquakes over 7.0. GPS can measure actual distances the earth moves during an earthquake, Pirenne says, which allows for a much more precise magnitude estimate for the large events.

The third unique element is the system’s architecture. Because many of the onshore sensor sites are remote with poor communication capability, they are designed with computers on site to combine and analyze the data from the GPS and accelerometers. This means those sites feed only results in small “communication bursts” to the larger system, Pirenne explains.

The data centre receiving those results uses an algorithm to triangulate the earthquake and then send the warning to the system’s subscribers.

Image: Ocean Networks Canada

On land, the isolated sensor sites generally have solar panels, a small battery box, computer and basic routing and communication devices. The underwater sites involved drilling a hole in the ocean floor, inserting a pipe, and feeding the sensor equipment into the pipe. Glass beads fill the pipe to improve connectivity between the instrument and the ground. The site is then cable-connected to ONC’s NEPTUNE cabled ocean observatory.

The ONC system is now working effectively in real-life situations. On April 13 this year, it detected a quake within the Explorer plate near the Neptune observatory. The system notified about the ground-shaking waves 89 seconds before they were felt in major West Coast cities.

“We had one of these typical medium-size earthquakes occurring at the border of the Juan de Fuca plate – it was not the Cascadia subduction zone, it was just nearby. Every year we have a couple of those magnitude five or six occurring on average,” Pirenne says. “We picked it up and announced it. It functioned as expected.”

The early warning system, once fully launched, will have direct subscribers such as ProTrans, the company that operates the Canada Line Skytrain in Vancouver. The earthquake notifications are sent directly to ProTrans’ control centre where they are being used to respond to an event following standard operating procedures that take into account the expected shaking intensity on location and the time available before shaking starts.

A national picture

Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) has been monitoring earthquakes since the late 1800s.

Earlier this year, NRCan announced that the national earthquake early warning (EEW) system will be operational in 2024, with an expected spring launch. The EEW will use data from more than 400 seismographs monitoring ground movement in seismic risk regions across the country, primarily western B.C., eastern Ontario, and southern Quebec.

NRCan seismologist Alison Bird called the early warning system a natural extension of their role as the authority on earthquake monitoring in the country. “EEW is exciting because it’s an incredible technology that can make a difference – reducing damage, injuries, and fatalities in major earthquakes,” Bird says.

In advance of the system launch, NRCan is funding eight new network extension, capacity, and research and development projects, which includes new sensor equipment and stations, new community technical co-ordinators, research, public education, and software developments.

Once fully operational, the national earthquake early warning system will be generating public alerts via the National Public Alerting System for the more than 10 million people in earthquake-prone regions of Canada. Bird says the EEW messages can also go to critical infrastructure operators and industrial facilities to trigger on-site automated response technologies, which can open doors, sound alarms, close valves, stop trains, and halt industrial processes.

Data will be shared between the Canadian national and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) earthquake early warning systems, facilitated by USGS software, to enable more accurate and timely alerting for earthquakes in the border region, Bird says.

“Once the national system is launched in spring of 2024, the combined systems will provide greater early warning coverage for North America than ever before,” she says.

“Protecting lives is at the core of the USGS mission” Robert deGroot from the USGS Earthquake Science Center said in an email to Avert. “It is exciting to partner with NRCan as they develop and roll out the Canadian national earthquake early warning system. In addition to sharing technical information, NRCan and USGS also collaborate on social science studies and education products that will benefit EEW users in both countries.”

NRCan said in a news release that if an earthquake similar to the 1700 megathrust quake occurred today the early warning system could provide up to four minutes of warning before the strongest shaking begins for people living near the opposite end of the subduction zone.

With four minutes, many lives might be saved.

Learn more about the ONC earthquake early warning system, as well as the ONC’s tsunami and flood risk inundation modelling, at oceannetworks.ca.

Learn more about the national earthquake early warning system at earthquakescanada.nrcan.gc.ca/eew-asp/system-en.php.

Print this page