DEMCON speakers talk climate change, community resilience, disaster response and recovery

November 14, 2023

By Elena De Luigi

Bernie Derible, Deputy Minister and Commissioner of Emergency Management Ontario. Photo: Annex Business Media.

Bernie Derible, Deputy Minister and Commissioner of Emergency Management Ontario. Photo: Annex Business Media. Emergency managers from across Canada wrapped up a successful two-day conference in Toronto in late October, which focused on new initiatives, lessons learned and best practices on topics including disaster response and recovery, community resilience and climate change.

Delegates were able to network and listen to more than 30 sessions with speakers from across North America at the Ontario Disaster and Emergency Management Conference (DEMCON) which offered keynote speeches, panel discussions, workshops and interviews.

Bernie Derible, Deputy Minister and Commissioner of Emergency Management Ontario, kicked off Day 1 with a keynote urging municipalities to convene on shared emergency management priorities, such as training and public education. “Invite us to your table,” Derible told the audience, suggesting the province can help fund and guide new community-level initiatives.

Ontario recently launched the Ontario Corps, a volunteer portal to train and identify volunteers willing to assist during an emergency. Derible called the initiative an “Ontario approach” to disaster NGOs. “It’s about the community,” he said.

In response to a question about provincial support for municipal emergency management jobs, Derible said that while the provincial government cannot fund a dedicated emergency manager in every municipality, it can help fund regional emergency managers who are responsible for a group of municipalities.

Solar emergency

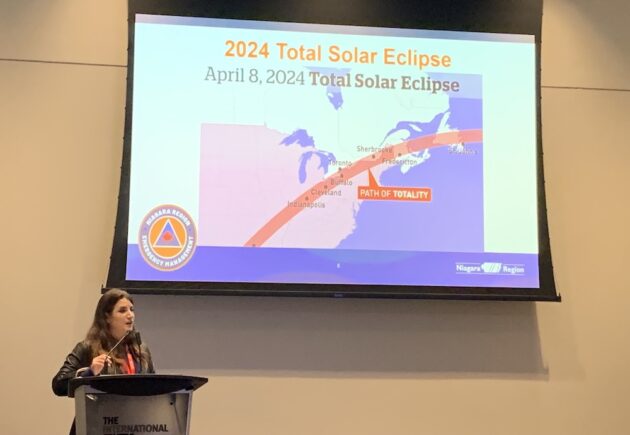

One of the first sessions at the conference discussed the upcoming total solar eclipse that will occur in Canada on April 8, 2024. Patricia Martel, community emergency management co-ordinator for the Niagara Region, talked about how an unsuspecting event can become an emergency.

This type of complex emergency is one that requires a unified and co-ordinated approach among emergency management at all levels of government because significant planning and preparedness are integral to ensure the event remains positive and to avoid disruptions to critical infrastructure.

The eclipse is expected to enter Canada in Southern Ontario – with the Niagara Region being in the path of totality – and then continue on through Quebec, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador.

Patricia Martel, community emergency management co-ordinator for the Niagara Region. Photo: Annex Business Media.

“What we did to prepare for this, since we knew it was coming, was taking a look at operational readiness. Where were the existing gaps and where can we actually work to fix them to the best of our abilities,” she said.

It is difficult to predict human behaviour, Martel noted, leaving it up to chance that people may gather for the total solar eclipse, but there are some concrete data points emergency managers can count on to help them better prepare for these types of events.

An example she discussed was the 2017 total solar eclipse that happened in the United States. That event saw huge mass gatherings, traffic congestion, and a frenzy of people looking up at the sky, waiting to see the exact moment when the moon passes between the sun and the earth.

Critical infrastructure and the local capacity of the area were strained, with mass influxes of people and historic traffic jams, among other concerns. Research completed after the event found that about 88 per cent of American adults watched the total solar eclipse either directly or electronically.

Indigenous communities

Darrin Spence, chair of the First Nations Emergency Response Association (FNERA), introduced his association at DEMCON. The organization, launched fewer than two years ago, has a mandate to ensure First Nations communities have their voices heard about the services given to them during an emergency.

FNERA wants to build capacity so that the economic spinoff from disaster management activities stays in the community rather than leaves with an intervening third party. That means they need to build capacity for preparation, mitigation, response and recovery within communities.

“There’s a lot of education that needs to happen. There are a lot of acronyms [to understand]. Our mission is to close that capacity gap and to build bridges,” Spence said.

A core component of building capacity is helping young people enter emergency management.

“We always have the youth leadership with us,” he said, pointing out young FNERA team members among the DEMCON audience. “These young people have it in them to lead, but they need the training and the support to develop that skill.”

The organization is also looking to facilitate respectful dialogue and part of that means changing the language of emergency management.

“I’m not going to call anyone a chief of operations,” he said. “Those people are called leads, firefighters are called fire keepers, and so on…We’re resilient, we always have been, and we’re still on survival mode.”

FNERA is one component of that survival to help decolonize emergency management in First Nations communities.

Elise DeCola, founding principal and general manager of Nuka Research. Photo: Annex Business Media.

One way that British Columbia is doing that is by revamping its emergency alert system, specifically for oil spills in First Nations communities. Current forms of notifying residents are labour intensive, unreliable, and inconsistent, said Elise DeCola, founding principal and general manager of Nuka Research.

However, a new pilot project the province launched is working towards making the alert system more efficient, reliable and consistent. The goal of the project is to increase spill preparedness and response in First Nations communities.

Alertable is a platform that sends out notifications to residents when there is an oil spill in the area. They can sign up with their phone or email address and set preferences for where they would like to receive the alerts, by email or text message.

“Where a nation might not have heard about something 16, 18 hours, two days into an incident in the past, they’re getting information really early. However, that doesn’t guarantee that a co-ordinated response starts at that moment,” DeCola said. “There’s still more work needed to build the collaborative management structures to really bring First Nations governments to the table early and often inside unified command to manage, particularly spills where we do have multi-jurisdictional command.”

A changing climate

Climate change reared its ugly head this summer with a record-breaking wildfire season and other extreme weather events taking place such as flooding and drought. Wildfires raged from coast to coast to coast. Thousands of people were evacuated, neighbourhoods were destroyed, and eight firefighters died in the line of duty.

David Pearson, project lead on climate change and science communication for Up North on Climate at Laurentian University, showed a room full of DEMCON attendees what Toronto would look like in the coming decades as climate change progresses.

Using a detailed map with scales for either “more climate change” or “less climate change”, Pearson made it clear that emergency management should involve more longer-term thinking, and about how cities are designed.

“The main problem with this conference is your thinking is too damn short. You’re not looking ahead at the problems, which will affect your children and grandchildren. And I think that’s a responsibility that you should take. Who else is going to take it? Climate change is important.

“Climate change is a creeping emergency. It’s not the sort of emergency tomorrow, or next month, or maybe next year,” he said. “It’s a creeping emergency with obviously, significant present emergencies that arise because of the progress of climate change. It’s important that you begin to think of the next generation and the generation after that.”

Explorer and storm chaser George Kourounis. Photo: Annex Business Media.

DEMCON wrapped up with a keynote speech from explorer and storm chaser George Kourounis. He shared some of his most dangerous expeditions with the audience, including hurricanes, tornadoes, volcanoes, active lava pits and the Middle East’s Darvaza gas crater, or “Doorway to Hell”, in Turkmenistan.

It was there that Kourounis dropped down into the burning natural gas field, which had collapsed into a cavern decades ago. He was the first person to set foot at the bottom of the crater in 2013.

“I’m finally suited up. We’ve done a whole bunch of tests. Eventually the moment comes down to literally taking one step, and you have to put 100 per cent trust in your risk assessment, your team, the equipment, the plan, everything,” he told the enraptured audience. “I stepped off the edge, and I felt like laundry drying on the line…standing at the bottom, surrounded by what I described as a Colosseum of fire in a spot where no one had ever stood before, really, to me felt like the closest thing that a human being can experience to standing on the surface of another planet, here on Earth.”

Print this page