How Nova Scotia’s EMO managed Atlantic Canada’s worst storm

October 5, 2023

By

Maria Church

Jason Mew and Lori Errington talk takeaways from their time leading Nova Scotia’s Emergency Management Office during post-tropical storm Fiona last year.

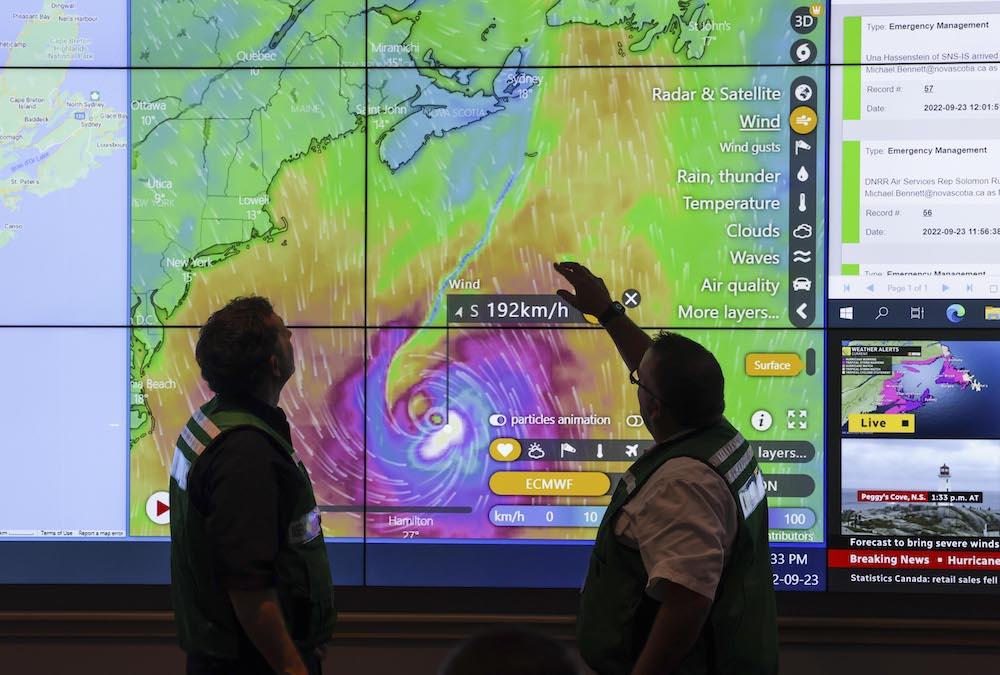

Jim MacDougall (left) and Andrew Mitton, incident commander with the Nova Scotia Emergency Management Office (NSEMO), look over the track of hurricane Fiona at the provincial co-ordination centre in Dartmouth, N.S. Photo courtesy Communications Nova Scotia.

Jim MacDougall (left) and Andrew Mitton, incident commander with the Nova Scotia Emergency Management Office (NSEMO), look over the track of hurricane Fiona at the provincial co-ordination centre in Dartmouth, N.S. Photo courtesy Communications Nova Scotia. Fiona was, in many ways, a first for disaster management in Atlantic Canada.

The hurricane-turned-post-tropical storm that hit the Atlantic provinces in late September last year caused unprecedented damage to trees, powerlines, and homes. Half a million people were without power for days. For thousands, it was weeks before the lights came back on.

Experts estimate Fiona was Atlantic Canada’s most costly weather event to date.

This is Nova Scotia’s story.

Tracking the storm

Emergency managers Jason Mew and Lori Errington were not new to the destructive force of hurricanes. Both leaders with Nova Scotia’s Emergency Management Office (NSEMO) were in their roles during hurricane Dorian in 2019 that was, until Fiona, the most damaging post-tropical storm the province had seen.

Mew is NSEMO’s director of incident management and Errington is the manager of planning and preparedness in charge of the provincial co-ordination centre (PCC). They together manage a team of about 24 full-time emergency mangers and specialists.

NSEMO tracks all Atlantic hurricanes as they form with direct advice from Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). Fiona was flagged as a potential hazard on Sept. 16, more than a week before the storm made landfall.

“Bob Robichaud – he’s a senior meteorologist with ECCC – he’s embedded with Nova Scotia EMO so he has an office here in our building and is instrumental in providing early warning for all these types of large events. He’s a great resource allowing EMO to not only track these storms, but to get a better idea on the possible impact and level of devastation we could see if the storm does make landfall,” Mew says.

Early trajectory estimates are known as spaghetti models because of all the predicted paths branching off according to different international forecasters. The models firm up as the storm approaches, but it can still veer off in the final hour.

“On a good day,” Errington says, “we’re expecting something to hit and then at the last minute it goes out into the Atlantic. Those are our good days.

“Fiona was not one of those good days.”

Andrew Mitton, NSEMO incident commander (left), discusses plans with NSEMO staff Dominic Fewer and Emily Riley at the provincial co-ordination centre in Dartmouth, N.S. Photo courtesy Communications Nova Scotia.

Making preparations

As the spaghetti models for Fiona began to narrow in likely landfall in Nova Scotia, NSEMO became a flurry of activity.

The PCC had a “soft opening” a couple days before potential landfall so staff could begin informing key partners such as utilities, wildfire crews and municipalities, giving them a heads up on the storm’s potential for impact, and suggesting they begin preparations.

“We have a list of 500 some odd contacts, ranging from municipalities to private sector partners in critical infrastructure,” Errington says. “We want our partners to be aware. They all get the same information at the same time.”

For Mew, the leadup days were consumed with briefings to external resources, including the province’s wildland fire crews and Nova Scotia Power. Both agencies were brought into the PCC in advance to set up incident command posts. “Their incident management teams take on a lot of our tactical response for large events like Fiona,” Mew says.

Team Rubicon Canada was another call made in advance of landfall. “It’s a new thing for us,” Mew says. “With Fiona, they were a great asset to reach out to and provided a great service. We were in contact with them a few days out and they had time to fly people in from all over Canada and had that team here a couple days before Fiona hit.”

Mew says his experience working in both the Canadian Coast Guard and the oil and gas industry taught him it’s better to be overprepared than underprepared. “It’s easier to deescalate than escalate. If you don’t have enough resources and an event hits – you’re already behind the ball trying to play catchup.”

On Sept. 23, the day before landfall, NSEMO activated the PCC at Level 1 (monitoring), with plans to escalate to Level 3 (full activation) the next day when landfall was expected.

Damage in Antigonish, N.S., from post-tropical storm Fiona. Photo courtesy Communications Nova Scotia.

Landfall

Fiona made landfall shortly after 3 a.m. with coastal windspeeds recorded up to 160 kilometres per hour. The storm caused widespread power outages from downed trees and damaged infrastructure. Dangerous conditions led more than 200 people to evacuate their homes in Cape Breton. Nova Scotia Emergency Health Services received its highest one-day call volume ever recorded.

Nova Scotia’s wildland fire team worked with the Emergency Management Office to co-ordinate more than 200 wildfire staff from across Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Quebec, who took part in the response, clearing downed trees and debris so that power could be restored.

By Sunday, more than 800 powerline technicians, forestry technicians and damage assessors were at work across the province.

Canadian Armed Forces personnel arrived in Nova Scotia Monday to aid the response and by mid-week more than 700 troops were clearing trees and debris. Team Rubicon’s Greyshirts arrived just before the storm and spent a total of 71 days in Nova Scotia doing similar cleanup work.

Mew estimates the PCC actively co-ordinated a few thousand responders during the first few days of Fiona. The total number of responders skyrockets when you consider private industry, municipal, healthcare and volunteer response from aid agencies such as the Salvation Army and Samaritan’s Purse.

“At one point our situation unit was taking over 1,000 emails per station, per day. It’s certainly busy in the PCC. It’s not uncommon to have over 100 people working in and around the centre any day or night,” Mew says.

The PCC stepped down from its Level 3 activation on Oct. 11, more than two weeks after the storm hit.

The storm destroyed a building in Glace Bay on Cape Breton. Photo courtesy Communications Nova Scotia.

Takeaways

The after-action report for Fiona has been completed, and NSEMO will be digesting lessons learned for years to come. Both Errington and Mew shared their own personal takeaways and lessons learned from both Fiona and Dorian.

Errington says a lesson learned from Dorian in 2019 and applied to the Fiona response was to include critical infrastructure technical specialists in the PCC during large events.

“It’s the interdependency piece. Fuel, for example. If fuel becomes a problem, it’s going to affect telecommunications. It’s going to affect first responders. Agriculture. Fuel and power are big rocks that affect the other sectors so much. We’ve embedded those specialists and that was a lesson learned from Dorian,” she says.

Dorian also prepared the NSEMO for the challenges of housing, feeding, sheltering and transporting the swell of responders in the province – a challenge magnified by power outages and business closures.

Pre-deployment of assets like Team Rubicon Canada helped buffer those challenges, Mew says. “It’s always good to get people here before the chaos starts,” he says. “Then these little issues that are little before the event – like connectivity with your computer, access to a printer, a room to work out of – everyone has time to troubleshoot. But in the middle of the event, or just after, people are a lot busier.”

Early preparations also allow NSEMO staff and other responders to get their affairs in order at home, Errington notes. “You have to start early for our own people to be able to take care of their own families, their own houses; to batten down the hatches and get supplies in for their loved ones so they can come here and focus on what they need to do,” she says.

A priority for Mew – and a common priority heard across the country – is to adopt national standards for training and exercises to allow for more sharing of resources.

“That’s why we’ve adopted ICS for a lot of the tactical aspects of the response that wildland fire uses. They can bring in wildland fire from any province or state in the U.S. and they all use the same system. They can easily integrate anyone,” he says.

“There is no such standard that exists in Canada for EMOs at this point. Hopefully in the future everyone will work towards a common standard so you can call in assistance.”

Mew says he’s seeing more EMOs adopting WebEOC from Juvare, a software they are now using for incident management.

Errington says a focus on good communication is an emerging theme in disaster management. “The ground truth coming in from the municipalities through the IMT or from us to the IMT, everybody should be communicating well. That’s why WebEOC is really going to be a part of our operations. Making sure people are getting the right information at the right time, and it’s as accurate as it can be. That’s a critical piece of response,” she says.

For municipalities, knowing the processes to follow during a large event is essential to a successful response. NSEMO hosts regional and province-wide exercises and training throughout the year to prepare municipalities and test communications.

“It’s a cycle of continuous improvement: exercising, finding gaps, and looking to address those gaps. Sometimes it’s through technology, sometimes through training, and sometimes it’s additional resources like people,” Mew says. “Municipalities are on the front lines of this type of response. They’re the boots on the ground – the volunteer fire departments, emergency management co-ordinators, local police, public works.”

Exercises also give municipalities opportunities to develop relationships with local stakeholders who would be responding during a disaster.

“This should be happening before an event, so you have those relationships, so you’re not handing out business cards during an event. You know each other and work collaboratively to prioritize and manage that response as a whole,” Mew says.

Activations like Fiona are challenging work, but it’s what happens between incidents – the training, exercises, relationship building, and stakeholder engagement – that constitutes the real work of emergency management, Errington says.

“Those things are what you see come to fruition in the activations. It’s all that hard work we do all year,” she says.

Print this page